Geography & Distribution

Widespread in north-temperate regions, throughout Europe, Iceland, northern Asia - including Siberia and Korea - North Africa, and western North America. South Africa, Australia and New Zealand. In some places where introduced it is considered a pest species in native forests where it forms mycorrhizas with native trees, including species of Nothofagus, and adversely affects native fungi.

Description

The cap is at first hemispherical, covered by a universal veil which is whitish and somewhat warty, and expands gradually to measure 7-15 cm across. The mature cap is convex to flat, red or scarlet, more rarely orange to orange-red or fading to orange-yellow with age or in wet weather. It is striate (grooved) at the margin, and bears white, fluffy, scale-like patches of the universal veil, which may be lost with age or wash off in wet weather. The gills are free, white or whitish and closely spaced. The stipe (stalk) is 10-18 x 1-2 cm, white, cylindrical, usually slightly felty-scaly, with a well-developed, white or yellow-edged ring or annulus, and a bulbous base bearing scale-like remains of the volva. The spore deposit is white. The spores are broadly ellipsoid to subglobose, smooth, not amyloid (not darkening in iodine), and 8-12 x 6-9 μm in size.

Mycorrhizas and host trees

Like most Amanita species, as well as a wide range of other fungi, A. muscaria is ectomycorrhizal, forming an intimate, mutually beneficial relationship with the roots of its host trees. In its native range in the temperate northern hemisphere, its hosts include birches and various conifers, including species of Abies, Cedrus, Picea and Pinus. It has long been established outside its native range in parts of the southern hemisphere, especially in south-eastern Australia, including Tasmania, and in New Zealand. Here, it has spread from the cultivated pine plantations (Pinus radiata), with which it was apparently originally introduced, to form associations with various other introduced trees, including broad-leaves, conifers and Euclayptus. In New Zealand it has become established with Nothofagus and possibly other trees native to the area, and may aggressively compete with, and oust, native ectomycorrhizal fungi. It is regarded as a pest species in New Zealand.

Uses

Fly agaric is well known to contain psychoactive alkaloids, and has a long history of use in Asia and parts of northern Europe for religious and recreational purposes. It has also been identified with ‘Soma’, a sacred and hallucinogenic ritual drink used for religious purposes in India and Iran from as early as 2000 B.C., and the subject of a Hindu religious hymn, the Rig Veda. The identity of Soma is controversial but is thought by the American author

Robert Wasson to be made from A. muscaria.

Since medieval times, fly agaric has also reportedly been used to attract and kill flies, and the ibotenic acid it contains is indeed a weak insecticide.

Robert Wasson to be made from A. muscaria.

Since medieval times, fly agaric has also reportedly been used to attract and kill flies, and the ibotenic acid it contains is indeed a weak insecticide.

According to the British mycologist John Ramsbottom, it was also used in England and Sweden for getting rid of insects.

Other anecdotal uses of fly agaric include its use as a treatment for sore throats, and arthritis, and as an analgesic. Fruit bodies also provide an important food source for invertebrates, especially for the larval stages of a range of Diptera (flies), particularly in the families Anthomyiidae, Cecidomyiidae, Heleomyzidae, Mycetophilidae, and some Syrphidae.

Other anecdotal uses of fly agaric include its use as a treatment for sore throats, and arthritis, and as an analgesic. Fruit bodies also provide an important food source for invertebrates, especially for the larval stages of a range of Diptera (flies), particularly in the families Anthomyiidae, Cecidomyiidae, Heleomyzidae, Mycetophilidae, and some Syrphidae.

Toxicity of fly agaric

Fly agaric is psychoactive and hallucinogenic, containing the alkaloids muscimol, ibotenic acid and muscazone, which react with neurotransmitter receptors in the central nervous system. These cause psychotropic poisoning which may be severe in some cases although deaths are very rare.

It also contains small amounts of muscarine, the first toxin to be isolated from a mushroom, and first isolated from this species. This causes sweat-inducing poisoning, stimulating the secretory glands and inducing symptoms which include profuse salivation and sweating. These symptoms can be treated by using atropine but this should not be used in cases of Amanita muscaria poisoning because it increases the activity of muscimol. It should be cautioned that faded specimens of A. muscaria, with orange caps, have sometimes been misidentified as Amanita caesarea (Caesar’s mushroom) which is a sought-after edible species found in southern Europe and North Africa. Is easily distinguished from A. muscaria by its yellow gills and large white volva.

Seven varieties:

var. flavivolvata is red, with yellow to yellowish white warts. It is found from southern Alaska down through the Rocky Mountains, through Central America, all the way to Andean Colombia.

var. alba, an uncommon fungus, has a white to a silvery white cap that has white warts but is similar to the usual form of mushroom.

var. formosa, has a yellow to orange yellow cap with yellowish warts and stem (which may be tan).

var. guessowii has a yellow to orange cap surface, with the centre of the cap more orange or perhaps even reddish orange. It is found most commonly in northeastern North America, from Newfoundland and Quebec south all the way to the state of Tennessee.

var. guessowii has a yellow to orange cap surface, with the centre of the cap more orange or perhaps even reddish orange. It is found most commonly in northeastern North America, from Newfoundland and Quebec south all the way to the state of Tennessee.

var. persicina is pinkish to orangish, sometimes called "melon"coloured, it is known from the southeastern coastal areas of the United States, and was described in 1977. Recent DNA sequencing suggests this may be a separate species which may require naming.

var. regalis, from Scandinavia and Alaska is liver brown and has yellow warts. It appears to be distinctive, and some authorities treat it as a separate species.

Treatment

Pharmacology

Muscarine, discovered in 1869, was long thought to be the active hallucinogenic agent in A. muscaria. Muscarine binds with muscarinic acetylcholine receptors leading to the excitation of neurons bearing these receptors. The levels of muscarine in Amanita muscaria are minute when compared with other poisonous fungi such as Inocybe erubescens, the small white Clitocybe species C. dealbata and C. rivulosa.

The level of muscarine in A. muscaria is too low to play a role in the symptoms of poisoning. The major toxins involved in A. muscaria poisoning are muscimol , an unsaturated cyclic hydroxamic acid) and the related amino acid ibotenic acid. Muscimol and ibotenic acid were discovered in the mid20th Muscarine, discovered in 1869, was long thought to be the active hallucinogenic agent in A. muscaria. These toxins are not distributed uniformly in the mushroom. Most are detected in the cap of the fruit, rather than in the base, with the smallest amount in the stalk.

The levels of muscarine in Amanita muscaria are minute when compared with other poisonous fungi such as Inocybe erubescens, the small white Clitocybe species C. dealbata and C. rivulosa.

The level of muscarine in A. muscaria is too low to play a role in the symptoms of poisoning. The major toxins involved in A. muscaria poisoning are muscimol , an unsaturated cyclic hydroxamic acid) and the related amino acid ibotenic acid. Muscimol and ibotenic acid were discovered in the mid20th Muscarine, discovered in 1869, was long thought to be the active hallucinogenic agent in A. muscaria. These toxins are not distributed uniformly in the mushroom. Most are detected in the cap of the fruit, rather than in the base, with the smallest amount in the stalk.

The levels of muscarine in Amanita muscaria are minute when compared with other poisonous fungi such as Inocybe erubescens, the small white Clitocybe species C. dealbata and C. rivulosa.

Symptoms

Fly agarics are known for the unpredictability of their effects. Depending on habitat and the amount ingested per body weight, effects can range from nausea and twitching to drowsiness, cholinergic crisis like effects (low blood pressure, sweating and salivation), auditory and visual distortions, mood changes, euphoria relaxation, ataxia, and loss of equilibrium.

In cases of serious poisoning the mushroom causes delirium, somewhat similar in effect to anticholinergic poisoning (such as that caused by Datura stramonium), characterised by bouts of marked agitation with confusion, hallucinations, and irritability followed by periods of central nervous system depression. Seizures and coma may also occur in severe poisonings. Symptoms typically appear after around 30 to 90 minutes and peak within three hours, but certain effects can last for several days.

In the majority of cases recovery is complete within 12 to 24 hours. The effect is highly variable between individuals, with similar doses potentially causing quite different reactions. Some people suffering intoxication have exhibited headaches up to ten hours afterwards. Retrograde amnesia and somnolence can result following recovery.

In the majority of cases recovery is complete within 12 to 24 hours. The effect is highly variable between individuals, with similar doses potentially causing quite different reactions. Some people suffering intoxication have exhibited headaches up to ten hours afterwards. Retrograde amnesia and somnolence can result following recovery.

Treatment

Medical attention should be sought in cases of suspected poisoning If the delay between ingestion and treatment is less than four hours, activated charcoal is given. Gastric lavage can be considered if the patient presents within one hour of ingestion.

There is no antidote, and supportive care is the mainstay of further treatment for intoxication.

If a patient is delirious or agitated, this can usually be treated by reassurance and, if necessary, physical restraints. A benzodiazepine such as diazepam or lorazepam can be used to control combativeness, agitation, muscular overactivity, and seizures. Only small doses should be used, as they may worsen the respiratory depressant effects of muscimol.Recurrent vomiting is rare, but if present may lead to fluid and electrolyte imbalances; intravenous rehydration or electrolyte replacement may be required. Serious cases may develop loss of consciousness or coma, and may need intubation and artificial ventilation.

If a patient is delirious or agitated, this can usually be treated by reassurance and, if necessary, physical restraints. A benzodiazepine such as diazepam or lorazepam can be used to control combativeness, agitation, muscular overactivity, and seizures. Only small doses should be used, as they may worsen the respiratory depressant effects of muscimol.Recurrent vomiting is rare, but if present may lead to fluid and electrolyte imbalances; intravenous rehydration or electrolyte replacement may be required. Serious cases may develop loss of consciousness or coma, and may need intubation and artificial ventilation.

Unlike psilocybin mushrooms, Amanita muscaria has rarely been consumed because of its toxicity and unpredictable psychological effects. Following the outlawing of psilocybin mushrooms in the United Kingdom, an increased quantity of legal A. muscaria mushrooms began to be sold for recreational and entheogenic use. In remote areas of Lithuania Amanita muscaria has been consumed at wedding feasts, in which mushrooms were mixed with vodka. The Lithuanian festivities are the only report that received of ingestion of fly agaric for recreational use in Eastern Europe.

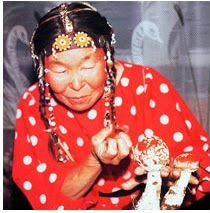

Siberia

Amanita muscaria was widely used as an entheogen by many of the indigenous peoples of Siberia. Its use was known among almost all of the Uralic speaking peoples of western Siberia and the Paleo siberian speaking peoples of the Russian Far East.

In western Siberia, the use of A. muscaria was restricted to shamans, who used it as an alternative method of achieving a trance state. (Normally, Siberian shamans achieve trance by prolonged drumming and dancing.) In eastern Siberia, A. muscaria was used by both shamans and lay people alike, and was used recreationally as well as religiously. In eastern Siberia, the shaman would take the mushrooms, and others would drink his urine. This urine, still containing psychoactive elements, may be more potent than the A. muscaria mushrooms with fewer negative effects such as sweating and twitching, suggesting that the initial user may act as a screening filter for other components in the mushroom.

In western Siberia, the use of A. muscaria was restricted to shamans, who used it as an alternative method of achieving a trance state. (Normally, Siberian shamans achieve trance by prolonged drumming and dancing.) In eastern Siberia, A. muscaria was used by both shamans and lay people alike, and was used recreationally as well as religiously. In eastern Siberia, the shaman would take the mushrooms, and others would drink his urine. This urine, still containing psychoactive elements, may be more potent than the A. muscaria mushrooms with fewer negative effects such as sweating and twitching, suggesting that the initial user may act as a screening filter for other components in the mushroom.

Soma

In 1968, R. Gordon Wasson proposed that A. muscaria was the Soma talked about in the Rig Veda of India, a claim which received widespread publicity and popular support at the time. He noted that descriptions of Soma omitted any description of roots, stems or seeds, which suggested a mushroom, and used the adjective hári "dazzling" or "flaming" which the author interprets as meaning red. One line described men urinating Soma; this recalled the practice of recycling urine in Siberia. Soma is mentioned as coming "from the mountains", which Wasson interpreted as the mushroom having being brought in with the Aryan invaders from the north. Indian scholars Santosh Kumar Dash and Sachinanda Padhy pointed out that both eating of mushrooms and drinking of urine were proscribed, using as a source the Manusmṛti.

Cultural depictions

The red and white spotted toadstool is a common image in many aspects of popular culture.Garden ornaments and children's picture books depicting gnomes and fairies, often show fly agarics used as seats, or homes. Fly agarics have been featured in paintings since the Renaissance. In the Victorian era they became more visible,

becoming the main topic of some fairy paintings.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment